UNBROKEN

They don’t make heroes like they used to. Instead of resilient men of remarkable deed, spirit and courage, we get the “selfie set,” principally remarkable for their inexhaustible ability to self-aggrandize.

But every so often along comes a story so extraordinary, redemptive and uplifting that even the most cynical can only be humbled and inspired to consider the stock from which we sprang.

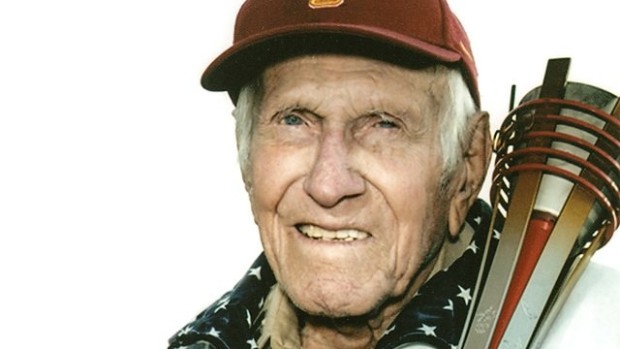

Such is the astounding story of Louis Zamperini, the late World War II veteran and Southern California man who grew up just north of San Diego in Torrance.

His is a story that could have easily fueled multiple movies, so Forrest Gump-esque were the diverse chapters of his long life.

Juvenile delinquent; world-class runner — who Adolph Hitler sought out at the 1936 Berlin Olympics; Army Air Corps bombardier, POW, alcoholic, born-again Christian, inspirational speaker, author, book subject and, finally, movie.

It’s hard to imagine so much life packed into one lifetime or the number of incredible highs and lows Zamperini endured in 97 years before his death last July.

Much of Zamperini’s story is depicted in the new film “Unbroken” — based on Laura Hillenbrand’s best-selling 2010 bio of the same name — that opened nationwide Christmas day.

If early returns are any measure, “Unbroken” has struck a cord with the public if not all critics. The film did a brisk box office in its four-day opening, pulling in $47 million at 3,100 theatres nationwide, including many here in military-friendly San Diego County.

As a side note, 700 World War II veterans are dying each day and now is a good time to consider their service and to ponder the stories that will be written and movies made about our modern combat veterans.

Regardless of what might follow, it is hard to imagine anyone ever trumping Zamperini’s amazing and motivating tale.

The son of Italian immigrants, he moved with his family to Orange County from New York shortly after World War I. At the time, Zamperini didn’t speak English and was bullied incessantly for it. He responded by getting fast with his fists. But it wasn’t until he funneled that passion into running that he left his shady – if not willful – days behind.

After setting high school and college track records, he made the 1936 Berlin Olympics at 19. Though he didn’t medal in the 5,000 meters, Zamperini final lap kick made such an impression on Hitler that he asked to meet the young American.

According to Zamperini, Hitler shook his hand, and said, “Ah, you’re the boy with the fast finish.”

Afterwards, Zamperini climbed a pole and stole Hitler’s personal flag.

Two years later, he set a college record in the mile with a time of 4:08 minutes, despite being severely spiked by competitors. His collegiate record would stand for 15 years and earn him the nickname “Torrance Tornado.”

The will succeed against the odds – coupled with an audacious disregard for authority – would both be credited with saving his life in the years that followed.

By late May 1943, Zamperini was a 26-year-old bombardier on a B-24 Liberator flying missions in the Pacific. One day his balky plane failed and the crew crash-landed in the ocean. Just three of the 11-man crew survived the ditching. Seven agonizing weeks later – weeks spent living on fish, unwary seabirds and predatory sharks that became prey — only Zamperini and another crewmember were still alive when the Japanese Navy captured them 2,000 miles from the crash site in the Marshall Islands.

Two hellish years of abuse at the hands of his Japanese captors followed in a series of POW camps, each worse than the last, where Zamperini was singled out for torture because of his track exploits.

It’s worth noting just how brutal Japanese guards were. In the European Theatre, one of every 100 U.S. POWs died while in German hands. In the Pacific under Japanese control, one out of every three American prisoners died.

While Zamperini’s status as a former Olympian made him too valuable to kill, he was singled out for constant beatings, humiliation, starvation and medical experiments.

Through it all, Zamperini survived using gallows humor, irrepressible spirit and a rebellious nature in the face of horrible conditions.

In August 1945 he was released at war’s conclusion.

Afterwards, he suffered from Post Traumatic Stress, drank heavily and dreamt of killing his captors. Zamperini credits evangelist Billy Graham with changing his life during a tent revival meeting in 1949.

In 1950, Zamperini traveled to Tokyo, sought up out his former captors and forgave them all.

In his later years, Zamperini would carry the Olympic Torch during the 1998 Nagano winter games and visit the Berlin Olympic Stadium, where he competed nearly 70 years before.

While “Unbroken” was in production, Zamperini died last July 2, in Los Angeles of pneumonia.

Zamperini wrote two memoirs about his amazing life, both entitled: “Devil at My Heels.” Though the books share the same name, they are substantially different.

Hillenbrand’s 2010 “Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption” reached bestseller status and Time magazine named it the top nonfiction book of the year.

On Christmas Day, “Unbroken” hit the theaters. Directed by Angelina Jolie, the movie tells Zamperini’s unparalleled story up to end of World War II.

Among his legacies: the Louis Zamperini Plaza on the campus of University of Southern California and Zamperini Stadium at Torrance High School.

Among Zamperini’s most widely used quotes:

“The one who forgives never brings up the past to that person’s face. When you forgive, it’s like it never happened. True forgiveness is complete and total.”

“All I want to tell young people is that you’re not going to be anything in life unless you learn to commit to a goal. You have to reach deep within yourself to see if you are willing to make the sacrifices.”

Rick Rogers is a longtime reporter based in San Diego. He can be reached at [email protected].